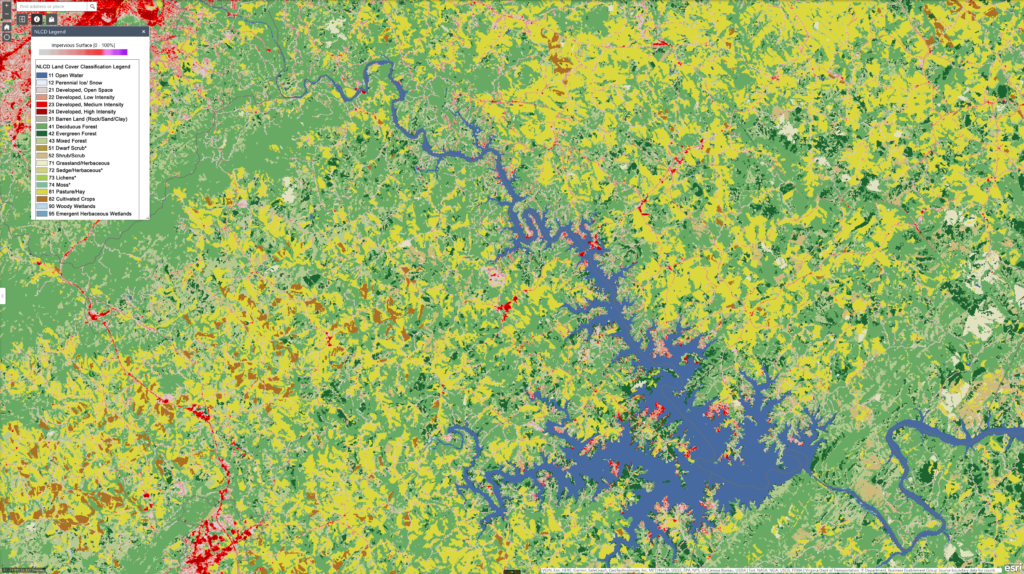

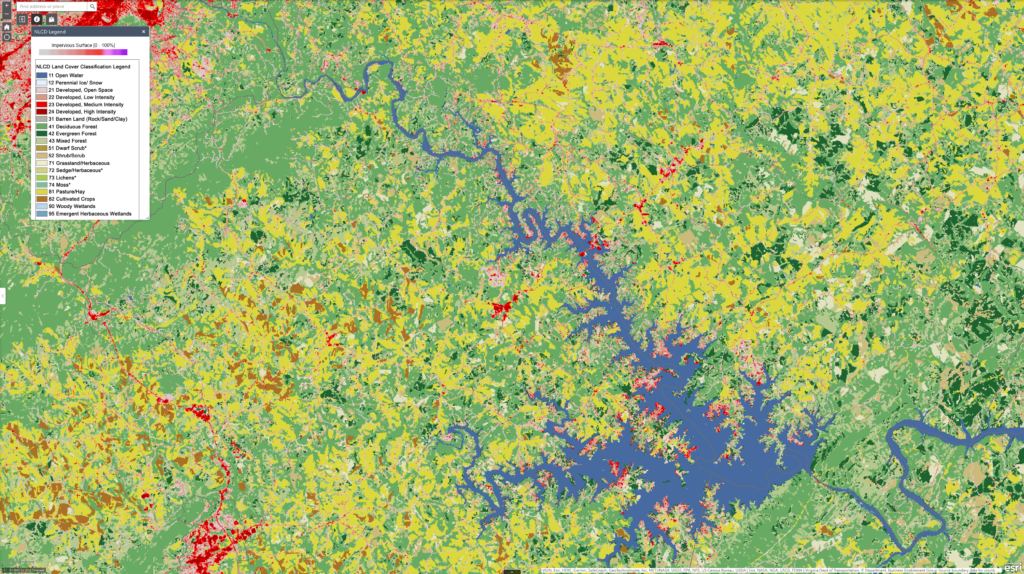

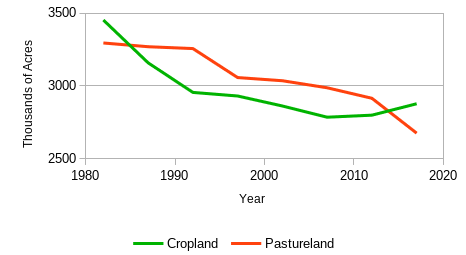

While we do not know the full set of causes of insect decline, nor the extent of the decline in all places, we do know that two of the most important causes of biodiversity decline in general are habitat loss and fragmentation. Virginia, one of the oldest states in the Union, has seen centuries of habitat change, and recent decades have brought only accelerated degradation from the perspective of the typical invertebrate. Land cover has swung from a natural state of forest through heavy logging and clearing of vast pasture and cropland expanses to the modern mixture of forest, field, and built environment. As our population continues to grow more land is developed—repurposed for impervious surfaces, dwellings, lawns, recreational facilities, retail and warehouse buildings, and industrial structures, and the infrastructure to support it all (see the maps below). Development consumes quality habitat for plants and animals alike. And the network of roads that invariably presages and then accompanies development has the effect of fragmenting the remaining patches of quality habitat into isolated islands.

The science of invertebrate conservation has crystallized around six principles, two of which address these causes:1

Principle 1: Maintain reserves of quality habitat.

Principle 6: Connect similar patches of quality habitat.

In short, in order to conserve Virginia’s invertebrates—in terms of both species richness and population—we need to protect and connect. This goes for both terrestrial and aquatic invertebrates, as well those with life stages in both worlds. Both these needs can be addressed through the establishment, restoration, and maintenance of invertebrate corridors through the degraded portions of the landscape.

In short, in order to conserve Virginia’s invertebrates—in terms of both species richness and population—we need to protect and connect.

Wildlife corridors are not a new idea. However, these efforts have historically been directed at conserving populations of large vertebrates which have very different needs, in particular different spatial needs, relative to invertebrates. Corridors for vertebrates need to be wide, and are designed to connect large tracts of quality habitat for animals with large territories and significant dispersal abilities. The corridors themselves generally do not serve as habitat. Invertebrates on the other hand are generally small, very small. Given the uncertainties in species and population, it’s hard to put a firm number on it, but the average or typical insect is on the order of a millimeter long. Most insects can fly, though most of those do not cover large distances. Many, whether winged or not, are quite slow dispersers. This means that, on the one hand, corridors do not need to be kilometers wide in order to serve as effective conduits between quality habitat patches; strips between 1 and 100 meters can be suitable. On the other hand, given that many invertebrates will not be able to disperse along a corridor of significant length over the span of a single generation, dispersal corridors must also constitute quality breeding habitat.

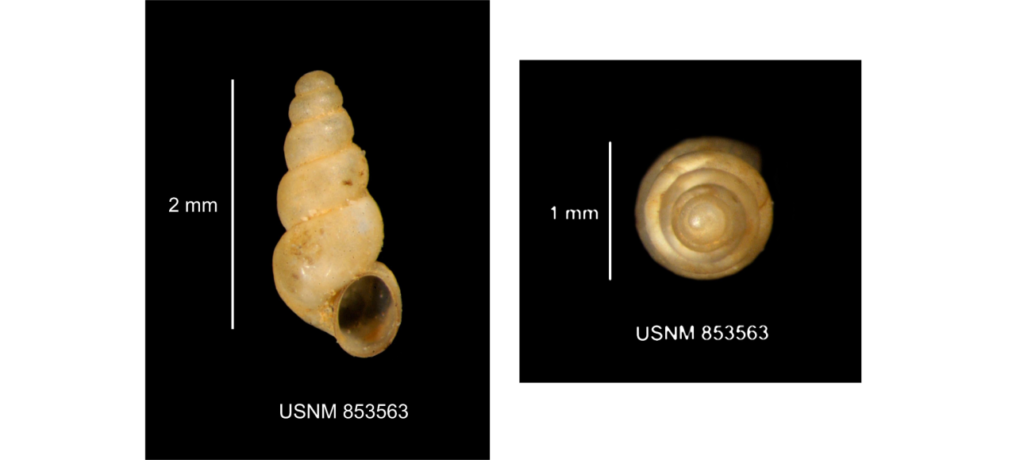

The calculus is a little different for aquatic invertebrates. In western Virginia, aquatic invertebrates dwell in numerous mountain creeks, rivers, and artificial impoundments ranging from cattle ponds to the massive Smith Mountain Lake. In the case of aquatics, connectivity is not always desirable. In particular, Virginia hosts a rich collection of stygobionts—aquatic animals endemic to the waters of our many limestone caverns. In particular, there are some 47 species of cave-dwelling invertebrates unique to one or another Virginia cave,2 and many more in the process of being described. What has generated such diversity is the separation of the waters of these cave systems, making each cave an island in a virtual subterranean archipelago, like an underground Galapagos. We obviously wouldn’t want to disturb that isolation. Similarly, it makes little sense to attempt to connect streams and rivers in distinct watersheds (though much work is being done to connect upstream and downstream regions of waterways fragmented by dams, weirs, and culverts).

Instead, we need to focus on improving the quality of degraded waterways. That is, for aquatic invertebrates, we must focus on protection more than connection. Importantly, however, the same set of tools can be brought to bear. Stream quality can be dramatically improved by focusing on relatively narrow bank margins. By managing the vegetation streamside—and shielding it from pesticides—we can reduce the flow of silt and toxic chemicals, both of which have dire consequences for aquatic invertebrates. At the same time, by protecting the margins of waterways, we provide habitat for the adult terrestrial stages of aquatic insects.

It is because of Virginia’s changing land use and consequent habitat loss and fragmentation that we need to protect and connect. But ironically, the manner in which development is taking place at present offers a unique opportunity for conservation. Specifically, Virginia is converting farmland—large farms are being sold off to be subdivided and developed. This provides ample opportunity to make strategic purchases or acquire easements to protect patches of quality invertebrate habitat. A field margin here, a stream bank there, or a strip of native vegetation through a suburban development can make a big difference. In short, VII has an opportunity to steer some of that land repurposing in a direction that will ultimately benefit invertebrate abundance and diversity.

With an eye toward cost efficiency, we are making the most of a dire conservation situation. Specifically, through strategic acquisition of land and easements, VII is working to:

- protect quality patches from development and degradation in such places as agricultural field margins, road verges, forest fragments, and subdivided farmland;

- establish linear corridors between remaining patches of healthy invertebrate habitat;

- manage corridors and patches to provide native vegetation free of pesticides to sustain maximal breeding populations;

- restore margins of waterways and remove physical barriers to stream connectivity:

- protect the headwaters of our mountain streams and the waters that feed the subterranean streams of our karst caverns.

References

- Samways, Michael J. 2007. “Implementing Ecological Networks for Conserving Insect and Other Biodiversity.” Insect Conservation Biology, 127–43. ↩︎

- https://virginianaturalhistorysociety.venn.studio/wp-content/uploads/sites/28/2022/12/Banisteria-42_Virginia_Cave_Inverts-1.pdf ↩︎